Posted by admin on June 22, 2017

The numbers are staggering. In 2015 alone opioid-related overdoses accounted for more than 33,000 deaths — nearly as many as traffic fatalities. Today more than 2.5 million adults in the U.S. are struggling with addiction to opioid drugs, including prescription opioids and heroin.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention:

- About 91 Americans die every day from an opioid overdose (that includes prescription opioids and heroin)

- Drug overdose deaths and opioid-involved deaths continue to increase in the United States

- The majority of drug overdose deaths — more than six out of 10 — involve an opioid

- Since 1999, the number of overdose deaths involving opioids — including prescription opioids and heroin) quadrupled

- From 2000 to 2015 more than half a million people died from drug overdoses

- In 2014, almost 2 million Americans abused or were dependent on prescription opioids

- Many people receiving prescription opioids long term in primary care settings struggle with addiction, ranging from 3 to 26 percent in a review by the CDC

- Every day, more than 1,000 people are treated in emergency departments for misusing prescription opioids

How did we get here?

In 2015, among 52,404 drug overdose deaths, 33,091 were from opioids that physicians prescribe such as hydrocodone. Studies suggest most of these involve diversion of legally prescribed pills, but some people died of the pills prescribed to them. Increasingly, as officials from the CDC recently testified before Congress, it is illicit drugs such as heroin and fentanyl that account for a rising tide of deaths.

Tracing America’s opioid epidemic goes back some experts say to the Roaring Twenties – a time when flappers danced to hot jazz, bootleggers sold black market alcohol in speakeasies run by mobsters, and morphine was handily prescribed for anxiety and depression.

“Opioids have been around for a very long time. Even back in the 1920s if you had depression or anxiety and you went to the doctor, you were likely to be prescribed a morphine-like medication,” said Daniel Doleys, PhD, clinical psychologist, director and owner of The Doleys Clinic in Birmingham. “Narcotics and opioid compounds do tend to stabilize different psychiatric problems, so oftentimes when we are prescribing these to patients, we think we are treating pain, but we may inadvertently be treating these underlying problems. The significance being that the patient may not show much improvement in pain or functioning, resulting in a lowering of the dose. This, however, can lead to re-emergence of the psychiatric symptoms and a plea from the patient and family to restore the medicine to its previous level. The potential impact of opioids on psychiatric symptoms, such as anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, PTSD, and how this relates to the prescribing and overuse of opioids has not gotten much attention.”

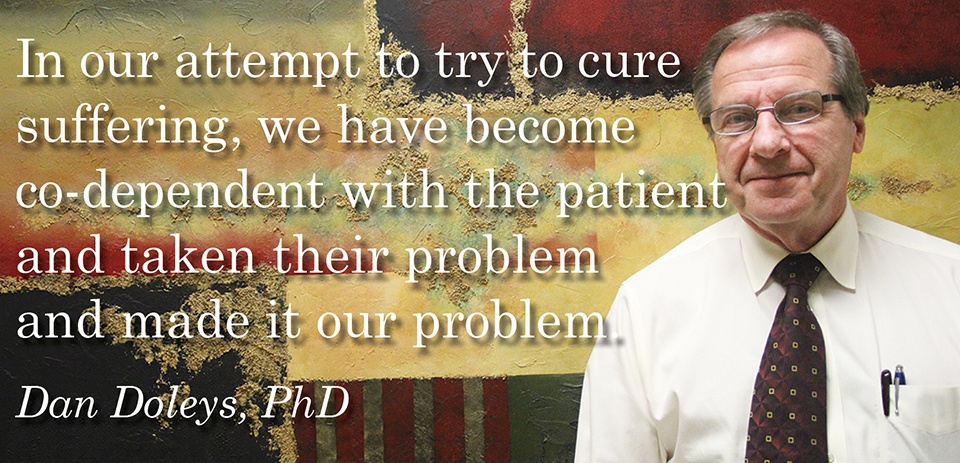

According to Dr. Doleys, the altruistic nature of medicine itself could be one of the primary factors involved in today’s opioid crisis. Physicians are trained in the healing arts and simply want to heal their patients.

“You cannot cure suffering, and that’s part of the problem. You have a lot of well-intended clinicians who feel their job is to cure suffering. But, you cannot cure all suffering,” Dr. Doleys explained. “A certain amount of suffering is not necessarily a bad thing. It motivates us; it drives us. In our attempt to try to cure suffering, we have become co-dependent with the patient and taken their problem and made it our problem. So, we’ve communicated with the patient that I have something here that I’m going to give you. We will start with two of these pills a day. It may or may not be enough, but we’ll see. The message to the patient may be, if two isn’t enough, we can increase the dose. The often unrecognized position assumed by the well-meaning doctor is that I’m committed to saving this patient from suffering, and if this patient is still suffering, then I need to keep going until I find a cure.”

More emphasis needs to be placed on clarifying expectations, goals and patient responsibilities as it relates to their treatment. All too often patients are allowed to become ‘passive recipients rather than active participants’ in their treatment, according to Dr. Doleys.

What is so special about opioids?

In 1986, pain specialists Russell K. Portenoy and Kathleen M. Foley published “Chronic Use of Opioid Analgesics in Non-Malignant Pain: Report of 38 Cases” in the journal Pain.

“We conclude that opioid maintenance therapy can be a safe, salutary and more humane alternative to the options of surgery or no treatment in those patients with intractable non-malignant pain and no history of drug abuse,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Doleys said of the study that with 67 percent of patients reporting a fairly good outcome with little adverse effects, although at doses much smaller than we typically see today. The study became “the lightbulb” that began a trend for opioids, which were originally prescribed only for malignant pain, to be used with other types of chronic pain.

“Questions soon began about how our bodies have these receptors which we already know will react to specific medications. We have these medications, but we are not helping people who are suffering and dying with pain,” Dr. Doleys said. “There was an increased awareness of people in pain from other sources rather than cancer, and the concerns began to grow about the under-treatment of pain, and some concerns were valid and almost criminal.”

In the 1980s, physicians began facing mounting pressures from not only their patients who were suffering from chronic pain issues, but also from advocacy groups and the federal government over the under-treatment of pain as a serious medical issue. By this time, there were about 100 million Americans reportedly suffering from chronic pain-related issues, according to the Institute of Medicine. With advertisements blasting away on television further advocating for the treatment of pain and applying even more pressure to the medical community to aggressively treat chronic pain, physicians were caught in the middle.

Pharmaceutical companies saw an opportunity and began producing more and more opioid medications, touting these new medications to physicians and federal regulatory boards as being safer than other painkillers on the market at that time. Unfortunately, this was not the case. When the dust settled and some of these companies were brought to court over their false advertising claims, millions of patients were addicted to their products.

Where the pendulum of prescribing opioids once swung toward over-treating chronic pain issues is now swinging back in a new direction, new issues are being uncovered – specifically addiction.

How opioids kickstarted the national conversation of addiction

“There is one positive outcome of the opioid epidemic. It has raised the awareness and acknowledgment that addiction is a disease. A national conversation has been initiated as a result of the severity, morbidity and mortality associated with opioid misuse and addiction,” explained addiction medicine specialist James Harrow, M.D., PhD. “We have been reluctant to acknowledge that addiction is a chronic, primary brain disease as opposed to what many people still believe is a voluntary process and that sufferers can just stop. That’s not the way it works. It is a biopsychosocial-spiritual disease that is chronic, relapsing and potentially lethal.”

According to Dr. Harrow, addiction is no different than other chronic diseases such as diabetes, asthma or hypertension. Addiction is preventable and when a patient has the illness, it is treatable with resultant long-term abstinence and remission. Those who are affected will be at risk of relapse to their drug of choice or other substances including alcohol for their lifetime. One of the problems we encounter is that addiction medicine is not taught in medical school.

“Medical education provides little to no training for what is probably the most prevalent disease in our nation today,” Dr. Harrow said. “The teaching of addiction is beginning to develop gradually within medical schools. However, if we do not educate medical students early in their training, then it is more difficult to assimilate the understanding of the disease when they enter practice.”

As with any other disease, physicians are not immune to the disease of addiction. Looking at the national population of physicians in the United States, roughly 900,000 doctors, the lifetime prevalence of addiction of practicing physicians is around 15 percent or about 135,000, Dr. Harrow said.

“Physicians may see themselves as superhuman, but that’s not the case. They may not be able to see themselves as being able to have these diseases, but they can and do,” Dr. Harrow said.

Because physicians face the same diseases as the patients, including addiction, that’s where the Alabama Physician Health Program steps in. APHP was created by the Alabama Legislature as a means for the Alabama Board of Medical Examiners and the Medical Association to address problems such as chemical dependence or abuse, mental illness, personality disorders, disruptive behaviors, sexual boundaries, etc. All information is privileged and confidential. The success rate of APHP for five years of monitoring is 85-90 percent with physicians successfully returning back to practice versus the long-term success rate of other programs of about 60 percent.

A clinical tool to aid in the war on opioid abuse

The Prescription Drug Monitoring Program is housed in the Alabama Department of Public Health and developed to detect diversion, abuse and misuse of prescription medications classified as controlled substances under the Alabama Uniform Controlled Substances Act. Under the Code of Alabama, 1975, § 20-2-210, et.seq, ADPH was authorized to establish, create and maintain a controlled substances prescription database program. This law requires anyone who dispenses Class II, III, IV and V controlled substances to report the dispensing of these drugs to the database.

Mandatory reporting began April 1, 2006. For those physicians who are eligible to use the PDMP, but are not yet registered, access is easy. Registering to access the PDMP database can be done by:

- Go to www.adph.org/pdmp

- Click on PDMP Login found in the orange menu banner on the left

- Click on Practitioner/Pharmacist

- Click on Registration Site for New Account

- Enter newacct for the User Name and welcome for the Password

- Complete the registration form and click on Accept and Submit

You will receive two emails when your application is approved; one with your user name and a second with a temporary password. Each physician can designate two delegate users per office. These delegate users have their own usernames and passwords to access the PDMP system.

If you have trouble using the PDMP, help is at your fingertips. Assistance with passwords, connection issues, search and query issues, and most other PDMP problems is just a phone call away at (855) 925-4767 and follow the prompts or by email at alpdm-info@apprisshealth.com.

The Alabama PDMP anticipates switching to new software later this year. The new software is user-friendly and has additional features that will aid prescribers and dispensers in making the best clinical decisions for their patients. More information about training will be emailed to users in the coming months.

Where do we go from here?

It would seem there’s a story on the news every day about opioid abuse. A new statistic, a new arrest, a new death toll, yet no new solutions even though every state and every organization has a task force or study group working on the nation’s epidemic.

Stefan Kertesz, M.D., MSc, is associate professor at the University of Alabama-Birmingham School of Medicine and director of the Homeless Patient-Aligned Care Team at the Birmingham Veterans Affairs Medical Center. His 20-year career has combined research and clinical care focused on primary and addiction care of vulnerable populations with funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. In 2016, he provided peer-reviewed and public media reviews of several facets of the opioid crisis, the rise of illicit fentanyl and heroin deaths, and how new policies affect patients with pain conditions. He may not have any new solutions, but his close study of the opioid epidemic has uncovered some interesting insights.

“We as doctors played a significant role in developing the opioid market, even though at this point we’re not the ones sustaining it,” Dr. Kertesz said.

In fact, one of Dr. Kertesz’s chief concerns stems from the revised CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, issued in March 2016, which might have caused a “pendulum swing” from the status quo of prescribing of opioids for chronic pain to a stricter guideline for their use. The CDC Guideline provides recommendations for primary care physicians who are prescribing opioids for chronic pain outside cancer treatment, palliative care and end-of-life care. This pendulum swing toward an effort to curb prescribing habits might be putting more patients at risk than physicians might know.

“As physicians today execute a hard shift on opioids, I plead for caution,” Dr. Kertesz said. “Patients with chronic pain have reported enormous suffering, some committing suicide as they see their lives turned upside down by doctors pressured to reduce their medications. Opioid prescribing ran up even more because of the use of the pain score…a subjective single number. Now there is an emergence of academic physicians who have dedicated their work to fighting addiction, including some who even worked on the CDC Guideline. They see that clinical practice has sprung ahead of data, that it has begun to look like someone has shouted fire in a crowded theater, creating a social stampede. This does not reflect the cautious, patient-centered care urged by the CDC.”

Dr. Kertesz is not advocating a return to the old days of prescribing opioids. Far from it. He works in Jefferson County, one of Alabama’s hardest hit counties where deaths by heroin, fentanyl and other prescription medications are disturbingly high. In fact, he’s doing everything he can, short of shouting from the rooftops, to inform government officials and colleagues about changing the opioid epidemic. He’s written opinions and reports for STATNews, Pain News Network, Huffington Post, and Politico. He’s given interviews for state and national news agencies. He’s published numerous peer-reviewed papers and articles. And, earlier this year, he issued a briefing for Surgeon General Vivek Murthy. The message should be clear: We need a better message.

“Saying that opioids are just as addictive as heroin is fantasy, the same as solving opioid overdoses in doctors’ offices alone when most individuals with opioid addiction did not start out as pain patients,” Dr. Kertesz explained. “When Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy made an under-appreciated declaration that we cannot allow the pendulum to swing to the other extreme here, where we deny people who need opioid medications those actual medications, as an addiction professional, I agree.”

How the Medical Association continues to be a leader in the fight against Alabama’s prescription drug abuse epidemic

In Alabama, our situation is equally staggering. According to the Alabama Department of Public Health, 762 Alabama residents died between 2010 and 2014 due to drug overdose, which included prescription drug overdose. In 2014 alone, there were 221 deaths due to drug overdoses.

“A group of us from the Medical Association met with some DEA officials and sheriffs who told us that Alabama was number one for hydrocodone until 2001,” said Association President Jerry Harrison. “We fell out of the top slot for a few years, but we got it back. We recognized that Alabama was in a very bad place, and we knew we had to take action.”

The Medical Association helped pass legislation in 2013 to reduce prescription drug abuse and diversion. That legislation resulted in Alabama having the largest decrease in the southeast and third-largest in the nation regarding the use of the most highly-addictive prescription drugs.

In 2016 the Medical Association launched a new public awareness campaign called Smart & Safe, which is the only prescription drug awareness program in Alabama spearheaded by physicians. Smart & Safe promotes safe prescription use, storage and disposal of medication by providing helpful tips, news and educational opportunities online at www.smartandsafeal.org.

Last year, the American Medical Association also partnered with the Medical Association to create a new clinical tool in the fight against prescription drug abuse. The collaboration produced Reversing the Opioid Epidemic in Alabama: A Health Care Professional’s Toolbox to Reverse the Opioid Epidemic, a downloadable document housed on the Smart & Safe website, contains handy reminders about Alabama law pertaining to prescribing opioids, tips for disposal of medication, statistics and useful links.

“When we started the prescribing lectures, we encouraged physicians to prescribe dangerous combinations less. We discussed the impact of the combination of pain medications and nerve medications because adding together one and one does not equal two…one and one can equal three or four in the damage or the potential damage they do to the patients. We have presented this course to almost 5000 prescribers now, and we’ve had an impact there,” Dr. Harrison said.

This year marks the ninth year of the Association’s Prescribing courses. By the end of the year, the Association will have completed 31 courses, and until 2013 Alabama was one of the only states offering an opioid prescribing education course when the FDA developed the blueprint for Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies for producers of controlled substances.

“We have to as a medical profession realize what we were taught 18-20 years ago, that we were not adequately treating pain and to increase the dosage of the pain medicine until there is a side effect, is no longer adequate. When you wake up in the morning and the first thing you think about should not be to reach for your pain tablet before you have your breakfast because you have to get going. I often wonder just what’s causing your pain first thing in the morning?” Dr. Harrison questioned. “You have to question your patients and be honest with them: Is that your pain talking, or is that your opioid rebound pain? When you and your patients start to look at that from a different point of view, then you can work together to decrease the amount of opioids used. Life is not pain-free, and opioids are not a cure for pain. It’s like licking the red off your candy. You’re making it so that the pain medicine doesn’t work for you as well as it used to. The more you take now, the less it’s going to work for you in the future. We’re part of the problem. And, if we’re part of the problem, we should be part of the solution.”