Although women continue to break boundaries in politics, business and medicine, barriers still remain, which mean trailblazers will always be there to forge ahead.

In fact, Alabama’s first female medical trailblazer passed the Alabama State Medical Examination in 1891 catching the attention of The New York Times. Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson became not only the first woman to pass the 10-day written exam, but she was the first woman of any race to officially practice medicine in the State of Alabama. Dr. Johnson’s actions 126 years ago set the stage for female physicians in Alabama.

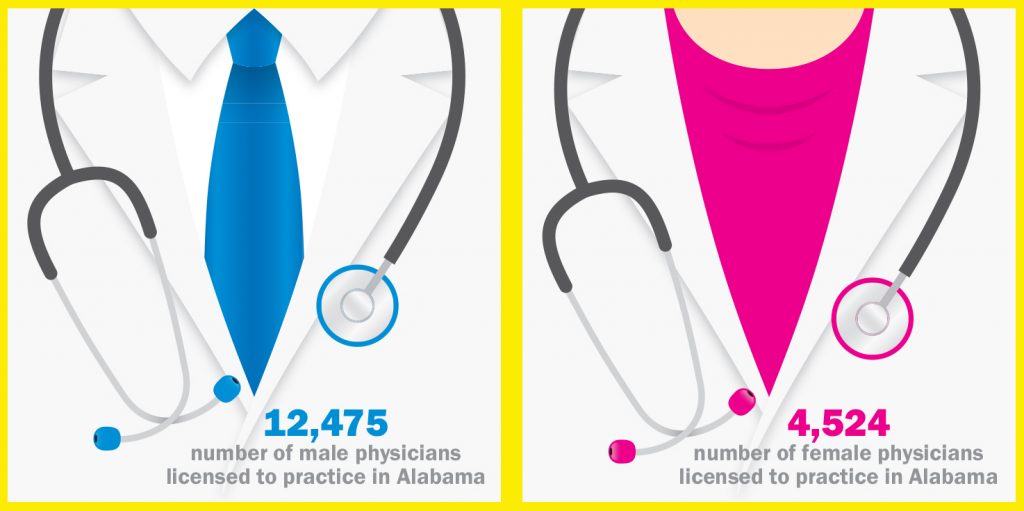

Today’s face of health care is changing. One would have been hard-pressed to find many women in medicine just a generation ago where now female applicants to medical schools make up about 50 percent of the total applicant pool. Nationally about one-third of American physicians are women, and with more female physicians come a few more, well…complications.

Women are wives and mothers, jobs which in their own right bring with them their own set of rules to be addressed, such as child care and maternity leave. Factor in the everyday stresses of being a physician, and it becomes complicated.

According to a 2014 study by the Association of American Medical Colleges:

- The proportion of applicants to medical school who are women has continued to drop since it peaked in 2003-2004 at 51 percent.

- Research indicates that many women who take part-time positions do so on account of dependent children, while most men take part-time positions due to holding other professional positions.

- Amongst full-time faculty, the only rank at which women account for more faculty than men is at the instructor level.

- While women residents increasingly enter specialties where they have been historically underrepresented, large gender disparities remain.

- The top 10 specialties for women residents in 2013-14 were OB-GYN, pediatrics, family medicine, psychiatry, pathology, internal medicine, emergency medicine, surgery, anesthesiology and internal medicine subspecialties.

The long working hours and dedication to delivering a high quality of health care to their patients take its toll on female physicians who are constantly striving to balance their work and home lives. According to a study by the Mayo Clinic and published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine in

2013, this struggle for a work/life balance is felt especially by those whose life partners also work, or by female physicians, younger doctors

and physicians at academic medical centers and manifests as burnout, depression and lower levels of satisfaction about their quality of life.

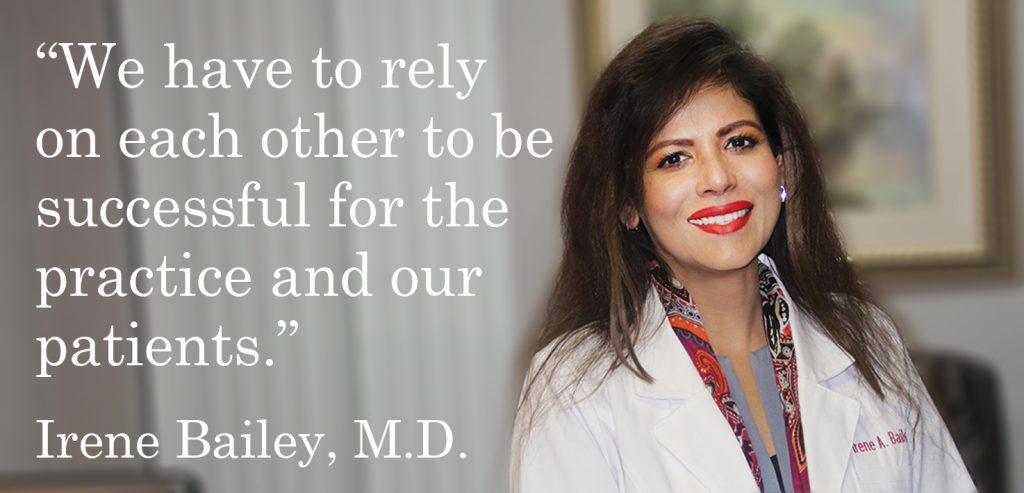

Finding that balance can be difficult but still possible, according to Irene Bailey, M.D., a family physician in Tallassee. Dr. Bailey and her husband are in the process are opening a new urgent and primary care facility in Montgomery that will be open seven days a week with extended hours.

“I always say, when you work, don’t work long hours that will sacrifice your family life. Budget your time. A lot of medical students and residents feel they have to work very long hours and have no personal life to be successful. But, that’s not true,” Dr. Bailey said. “I learned this rule from my attending, and I’m still living it today: Come to work at least 15 minutes early. You’ll have time to get a cup of tea or coffee and get your paperwork started. That 15 minutes is your head start on your day so you don’t rush before you see your first patient.”

Jennifer Dollar, M.D., a pediatric anesthesiologist in Birmingham, agreed with Dr. Bailey that going the extra step to plan out your schedule, especially for female physicians with busy schedules and families, is a necessary key to success.

“When I’m in the operating room, I may not have that ability to take the time out of the day that I would like to slow down a little. You have to be pretty wise about how you plan out your day. It’s the little things like bringing your lunch and thinking about the things you need to prepare yourself with for what your day may bring. Planning ahead is very important because you’ll still get pulled in a lot of different directions. Your patients need you, your staff, your family, and if you have administrative roles outside your practice…these are all things you juggle throughout the day that pull you in different directions,” Dr. Dollar explained. “I try to map out my week. I even try to map out my month in the very beginning just so I have some kind of idea of where I’m supposed to be and when and what kind of preparation I need before I get there. Then, when I toss in what my kids need, it gets really tricky. It’s a challenge of how do we get all of these moving pieces moving in the right direction to get everything accomplished.”

Unfortunately, in creating a balance between work and home, more importantly making time for their family, can cause some cracks in a female physician’s professional world. The decision then becomes how to speak up to make the situation better.

Lee Sharma, M.D., an OB-GYN in Auburn, found herself with that decision 16 years ago after working as a partner in an all-male practice in which she was the first female partner.

“I don’t think my partners were really prepared to have a female physician, much less a working mother, in the practice because it really is a different consideration when you have a child. My husband and I were already working our call schedules so we were never on call at the same time,” Dr. Sharma said.

Dr. Sharma admitted that when she joined the practice, she never thought of having a conversation with her partners about what would happen when she and her husband decided to have a family. But, when she became pregnant and took maternity leave, she said it was something not only she and

her husband had to adjust to, but her partners as well.

“I had to explain to them that I’m not like you. I do what you do and what your wife does on a daily basis. Because of that, there’s some other things that I have to have,” Dr. Sharma said.

She worked long, crazy hours for four years trying to make the best of being a partner in her practice, being a physician to her patients, and being a wife and mother at home. But, it was an early morning page from her husband that made Dr. Sharma realize just what she was giving up.

“I was on call at the hospital and my husband paged me at about 7 a.m., and he never did that unless it was an emergency. He told me that our youngest woke up around 2 a.m. and wanted to know where I was. He told her I was at the hospital taking care of the babies. She got the phone and asked him to ‘call Mommy.’ I was heartbroken. That was it. I could not have my children miss me like that again,” Dr. Sharma said. Shortly after, she resigned her partnership and opened her own practice.

Nina Nelson-Garrett, M.D., of Montgomery, chose a very male-dominated specialty when she opted for gastroenterology, but it was her passion. Although now she said she’s beginning to see more women enter the specialty, she’s worried for the profession as a whole.

“I’m finding that physicians are leaving medicine altogether. Some of it might be because of the changes in health care. I mean I’ve seen surgeons who are retiring early because of all these mandates,” Dr. Nelson-Garrett suggested. “For women, I think it’s a question of can I can continue at this pace and in this role?”

As an African-American female physician, Dr. Nelson-Garrett has faced different challenges, which she said she has looked at as changing the image of what a physician is to her patient – one patient at a time. From having patients expecting to see a male physician to coming face-to-face with a patient who admitted upfront that he was a racist. But, Dr. Nelson-Garrett’s personal motto, “one person at a time,” has bolstered her during some trying situations.

“I’ve had quite a few instances of being overlooked, ignored and downright mistreated, but I’ve had to just push through,” Dr. Nelson-Garrett explained. “I try to look at a challenging situation as an advantage, like what can I offer in this situation. Then, I want to change the image of what a physician is to our patients. You have to do that one patient at a time.”

Dr. Nelson-Garrett said that because she’s in a specialty where most of the physicians are men, it’s not uncommon for a patient automatically assume that because of her hyphenated last name, that Nelson is her first name and Garrett her last, the patient will often expect a male physician.

“I’ve even gotten nurse,” Dr. Nelson-Garrett chuckled. “Once in medical school during morning rounds huddle where I was the only female in the group, someone thought I was housekeeping. A patient’s family member walked up to me and asked me for a mop and asked if I could help clean up a room. I was shocked! My male colleagues spoke up very quickly and asked why that family member would ask that question. We were all together, with our white coats, and it was just strange. My colleagues were very supportive, but sometimes people assume incorrectly. I think it may be our history because for so long medicine was dominated by men. Somehow it’s become ingrained in patients to expect their physicians to be men.”

For Dr. Nelson-Garrett being a female physician may have its challenges, but she said she feels some of the challenges she’s had in her career have been framed by her race as well.

“In my life, I have never been able to untwine those two unchangeable parts of me,” she explained. “Patients want to know that you care about them, that you are listening to them, and that you are going to try to do something to help them. “When I was living in Arkansas I was taking care of a young man who told me he was racist. I told him my purpose was to take care of him that day. He had fairly significant liver disease, and it took a good bit to get his health under control. When I was getting ready to leave Arkansas, he came to my office and gave me a gift that I still have on my desk. It’s a stone that reads, ‘Nothing is ever etched in stone,’ because he wanted me to come back to Arkansas. No matter who we are, we want to know that someone cares about us.”

Here in Montgomery, Dr. Nelson-Garrett is chief of staff with Baptist East, and she said she has been extremely impressed with the administration’s willingness and respectfulness to have women in leadership positions.

Although each of these physicians have had their own personal struggles in medicine, they agree on one thing in particular for women in medicine today: Speak up.

Dr. Bailey, who’s now operating in two offices, is a firm believer in the power of teamwork. However, she admits it’s very easy for a woman’s nurturing tendencies to take over in the health care system and try to do everything herself.

“Be a team player from your front desk throughout the office. Your learning experience extends to your nurses. We are a team, and we work as a team. It’s important not to hold the burden of the day on our shoulders alone. We have to rely on each other to be successful for the practice and our patients,” Dr. Bailey said.

For Dr. Dollar, who’s the immediate past president of the Alabama State Society of Anesthesiologists, she said she never felt limited as a woman in medicine or excluded from activities by her male colleagues or administrators. But she really didn’t know what she was truly missing in her career until she was introduced to organized medicine.

“You go through medical school and residency to become the best physician that you can be, and your goal is always to take the best care of your patients that you possibly can. But, what I’ve also learned through organized medicine is that it’s not enough to get up every day to take excellent care of your patients. It’s just not enough. That makes you a great physician for the people that you interact with, but your patients also need you to speak up about policy issues that are going to affect them. Your patients don’t have a way to speak up or to understand the complicated issues affecting medicine or everything that goes into practicing medicine today. You have to be an advocate for your specialty. You have to be an advocate for your patients and their excellent care. There are a whole lot of people who have an interest in health care and in medicine who don’t understand how the rules are made or who those rules affect every day,” Dr. Dollar explained.

Dr. Nelson-Garrett’s personal mantra of ‘one person at a time’ extends far beyond the treatment room. Having a voice in the legislation of medicine is just as important as the practice of medicine, and for Dr. Nelson-Garrett, she believes that voice is as much of a physician’s job as treating a patient.

“When you’re part of a group, your voice is heard much louder. With all the changes in health care, a lot of people might feel that we didn’t have a real voice in how the change was made, and that’s where all the angst has come in,” Dr. Nelson-Garrett said.

Dr. Sharma, who found her voice while trying to reconcile a difficult situation, went so far as to get her Master’s degree in conflict resolution and was one foot out of the practice of medicine when she realized that it wasn’t medicine after all that was the problem.

“I started with the AMA when I was a med student. One of the things I’m most grateful for is to be able to serve on Graduate Medical Education Advisory Committee, and I was the only one speaking for the residents in that room. They were making changes to the residency training requirements, and I was the only one speaking up for the residents. What a lot of physicians don’t realize is that if they don’t speak for or against something, nobody will. Then, you can’t be surprised or upset when legislation gets passed that has anything to do with your patients. If you didn’t speak beforehand, you’ve got no right to complain. Doctors think it’s hard to get involved, but it’s not. All you have to do is to be willing to help. Doctors may not realize all that legislation we don’t want to deal with now will pass, and you’ll have to deal with it later,” Dr. Sharma said.

Article by Lori M. Quiller, APR, Director of Communications and Social Media