Despite years of warnings that older adults shouldn’t take sedative drugs that put them at risk of injury and death, a new study reveals how many primary care doctors are still prescribing them, how often, and where the practice is most prevalent.

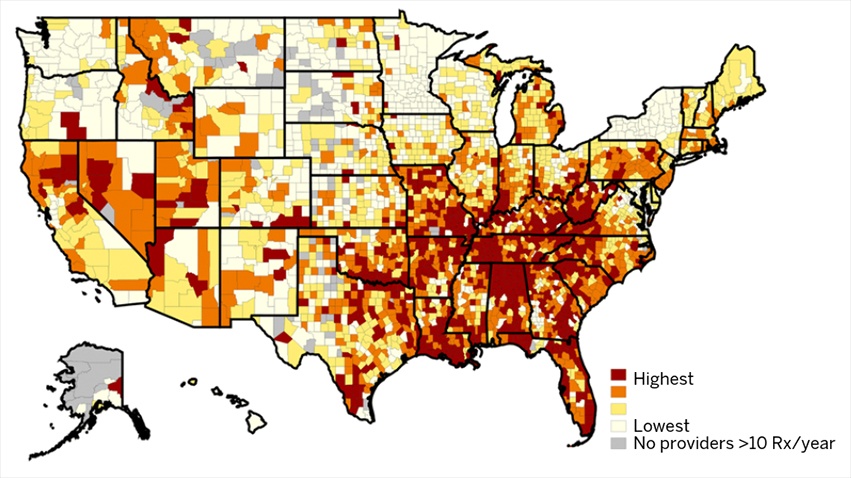

Mapped out county by county, the nationwide study shows wide variation in prescriptions of the drugs known as benzodiazepines. Some counties, especially in the Deep South and rural western states, had three times the level of sedative prescribing as those with the lowest levels.

The study, published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, also highlights gaps at the provider level: Some primary care doctors prescribed sedatives at a rate more than six times that of their peers.

Researchers found that top prescribers of drugs such as Xanax, Ativan and Valium also tended to be high-intensity prescribers of opioid painkillers.

The counties with the most intense sedative prescribing tended to have lower incomes, less-educated populations, and higher suicide rates, the study finds. They also overlap with other maps showing high county-level opioid painkiller prescribing.

“Taken all together, our findings suggest that primary care providers may be prescribing benzodiazepines to medicate distress,” says Donovan Maust, M.D., M.Sc., a geriatric psychiatrist from the University of Michigan who led the study with a team from U-M and the University of Pennsylvania.

“And since these drugs increase major health risks, especially when taken with opioid painkillers, it’s quite possible that benzodiazepine prescribing may contribute to the shortened life expectancies that others have observed in residents of these areas.”

Where prescriptions are highest

The study is based on data about all prescriptions written in 2015 by primary care providers for patients in the Medicare Part D prescription drug program. The researchers combined that information with county-level health and socioeconomic data from the County Health Rankings project, a project of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and University of Wisconsin.

In the single year studied, the 122,054 primary care providers included in the study prescribed 728 million days’ worth of benzodiazepines to their patients, at a cost of $200 million.

The states with the highest intensity of prescribing — which the researchers defined as prescription days of benzodiazepines relative to all prescribed medication days — were Alabama, Tennessee, West Virginia, Florida and Louisiana.

The states with the highest intensity of prescribing — which the researchers defined as prescription days of benzodiazepines relative to all prescribed medication days — were Alabama, Tennessee, West Virginia, Florida and Louisiana.

States with the lowest intensity were Minnesota, Alaska, New York, Hawaii and South Dakota.

Across all types of providers, primary care and otherwise, benzodiazepines accounted for 2.3 percent of all medication days prescribed to Part D participants by those providers that year.

Primary care doctors accounted for 62 percent of all benzodiazepine prescriptions. This confirms other findings that led Maust and his colleagues to focus on primary care providers in the new study. Previous studies have shown such providers account for the majority of benzodiazepines prescribed to older adults, a population much less likely than younger adults to see a psychiatrist.

Higher sedative prescription intensity was also associated at the county level with more days of poor mental health, a higher proportion of disability-eligible Medicare beneficiaries, and a higher suicide rate.

More about sedative risks

Benzodiazepines have often been prescribed to ease anxiety or insomnia, though several studies by Maust and others have shown that patients receiving the drugs often don’t have a formal diagnosis of either condition.

But the drugs come with a price: clouded thinking ability, higher risk of auto accidents, falls and fractures, and a tendency to hook patients into long-term use despite their intended use as a short-term treatment.

Benzodiazepines as a class are the second-most common group of drugs associated with medication-related overdose deaths, right behind opioid painkillers.

Such risks have landed benzodiazepines on the American Geriatric Society’s list of prescription drugs that people over age 65 should avoid, although their short-term use in treating anxiety or insomnia that haven’t responded to other options is still considered acceptable.

More about the study

To be included in the county-level study, a given primary care provider had to prescribe a benzodiazepine at least 10 times in 2015. The individual physician-level study looked at 109,700 doctors after excluding the 10 percent of prescribers who saw the fewest Medicare beneficiaries.

The researchers divided individual prescribers into four groups according to the intensity level of their benzodiazepine prescribing.

The range was large. For the lowest group, about 0.6 percent of total prescriptions were for benzodiazepines, compared with 3.9 percent for the highest-intensity group. That’s a 6.5-fold difference in benzodiazepine prescribing.

Those in the highest-intensity group were also likely to be high-intensity prescribers for opioids and antibiotics, and also for other drugs that have been classed as high-risk for older adults.

“That the same providers appear to be high-intensity prescribers of both medications is potential cause for concern,” says Maust.

Female primary care providers were less likely to be high-intensity benzodiazepine prescribers. The more years a physician had been in practice, the higher their chance of being a high-intensity prescriber.

Physicians with higher percentages of patients who were white or who received Extra Help payments available to low-income, low-resource patients under Part D of Medicare were also more likely to be high-intensity sedative prescribers.

Researchers could not see data down to the patient-level in the available Medicare data, so they couldn’t look at what conditions patients were listed as having, other clinical findings, or the patients’ individual social and economic status.

In addition to Maust, the research team included senior author Steven Marcus, Ph.D. of the University of Pennsylvania, and U-M Department of Psychiatry faculty L. Allison Lin, M.D., M.Sc., and Fred Blow, Ph.D. Maust, Lin and Blow are all members of the U-M Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation.

Funding for the work came from National Institutes of Health (AG048321, DA045705), the American Federation for Aging Research, the John A. Hartford Foundation, and the Atlantic Philanthropies.